PUNK Magazine’s 50th Anniversary

Founder John Holmstrom talks with Richard Boch about the downtown magazine that captured Punk's rise, as a new exhibition at Ki Smith Gallery marks the milestone with original artwork, covers, and classic photos from PUNK’s heyday.

Where did it begin and who was there? I’m not alone when I credit CBGB as the birthplace of Punk—the Bowery, circa 1975, certainly provided the fitting backdrop—ripe with a seediness and desperation ready to cry out with what would become Punk’s primal scream. Max’s Kansas City, the dissolute hipster hangout that opened ten years earlier and commonly referred to as Max’s, gave those screams and rallying cries another place to call home. Taking a moment and realizing hardly anyone outside a small collective of musicians, artists and troublemakers had considered the possibility of Punk, no less a magazine inspired by and dedicated to furthering its rag-tag existence, here we are fifty years later, celebrating PUNK Magazine and its founder John Holmstrom.

The early wave of proto-Punk—The Stooges, MC5, and New York Dolls, even Alice Cooper and the band Jack Ruby with George Scott III and violinist Boris Policeband—lit the fuse in New York City that made way for Ramones, Television, Patti Smith, Richard Hell, and the Dead Boys. It was around this time that the Punk scene in London launched a more politically armed sonic broadside by way of the Sex Pistols and Vivienne Westwood, followed by The Clash and The Damned. Regardless of who fired first, New York or London, misses the point. The truth is that Punk, over the course of the last fifty years, changed everything from music and art to literature, film and fashion. All it needed was someone to cover the sound, the vision, the mayhem and the scene—that’s where John Holmstrom came in.

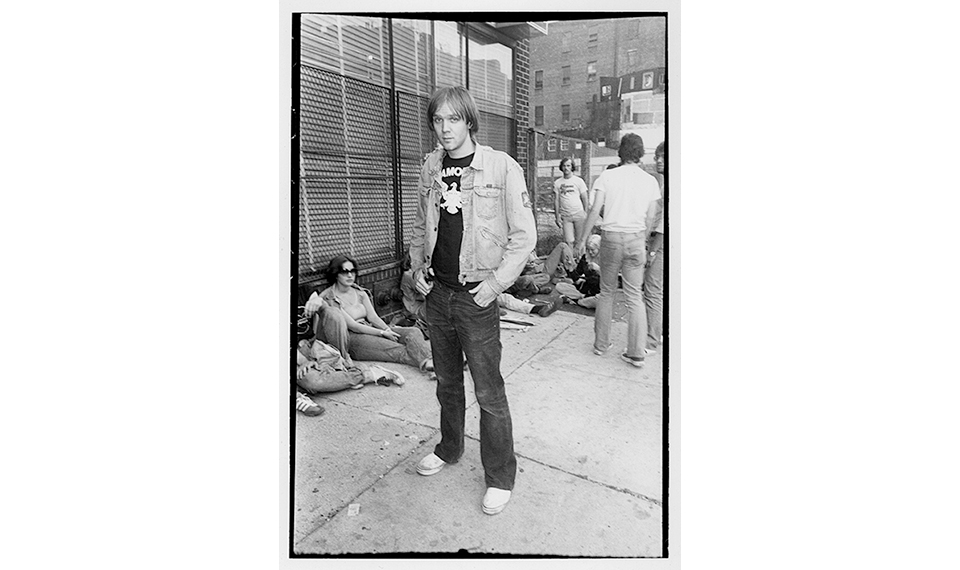

Holmstrom was a twenty-one-year-old kid originally from Cheshire, Connecticut. He studied at the School of Visual Arts, on New York City’s East Twenty-third Street, an indirect stepping stone to CBGB, the Bowery hole-in-the-wall that came to be Punk’s Mecca. John Holmstrom’s rough-and-tumble suburban-transplant look fit in perfectly with the loosely assembled cast of characters that filmmaker Amos Poe would soon capture in his own early Punk masterpiece, The Blank Generation.

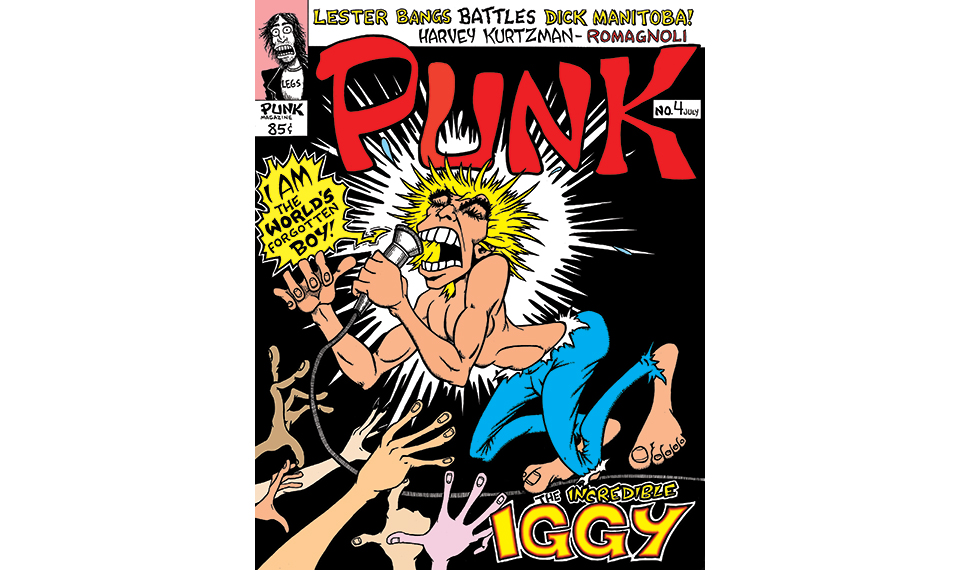

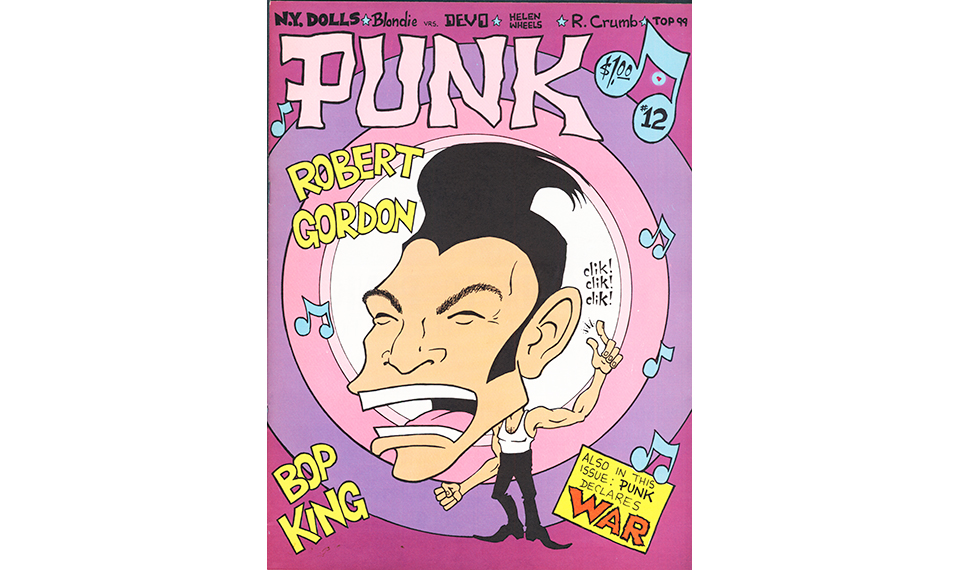

John Holmstrom’s talent as a cartoonist, draftsman, and accidental social anthropologist would serve him well, as he and his co-conspirators founded the groundbreaking magazine. Artistically offbeat, radically cartoonish and uniquely revolutionary, PUNK was oddly literate, provocatively sensational and sought after by fans, collectors and the curious yet deeply skeptical mainstream.

PUNK Magazine cast a wide net, depending on your definition of wide. Writers, musicians and photographers, including Richard Hell, Lester Bangs, Debbie Harry, and Roberta Bayley, along with so many other cutting-edge notables, all became instrumental in the magazine’s success. Issue #1, published in 1976, featured a spooky and bug-eyed Lou Reed whose pre-Punk bonafides and affinity for dark and dingy places dated back to his Velvet Underground days. Patti Smith was all over Issue #2, with Ramones and Blondie up next. Even Blue Öyster Cult and Bay City Rollers were tossed into the mix, adding a not-so-subtle twist of Punk attitude and humor to the previously noted wide net.

Taking a series of remarkable twists and turns, the PUNK Magazine archive and the papers of its founder, John Holmstrom, now reside in the Rare Book & Manuscript Library at Yale University, while elements of the magazine have both informed and been included in various museum shows. Time really does fly—as that old cliché likes to remind us—as we come to realize PUNK, the magazine founded in 1975 and publishing fifteen issues between 1976 and 1979, is celebrating its 50th Anniversary. An exhibition at Ki Smith Gallery in New York City to commemorate the occasion includes original artwork and covers, along with classic photos from PUNK’s heyday.

I recently had the opportunity to catch up and talk with John Holmstrom, so let’s let him tell us what PUNK at 50 is all about.

John Holstrom, 1977. Photo by Godlis

Richard Boch: Hi John. We talked about doing this interview several months ago, and it’s great we’ve been able to line it up with PUNK Magazine’s 50th Anniversary exhibition. I can only imagine how much work went into putting the show together, but I’m curious to know if friends and co-conspirators from PUNK’s early days were available and excited to be part of the celebration.

John Holmstrom: OK, there’s quite a few questions there—and yes, the work involved has been humongous—but I’ve wanted to stage the 50th anniversary (of PUNK Magazine) ever since the 40th! I was talking to a few people about a space for the show and found the Ki Smith Gallery through the photographer Bobby Grossman. When I heard Ki grew up (in the East Village) next door to the Ramones’ art director Arturo Vega, I was like, this is the place—and Ki’s been wonderful to work with. The big official opening will happen on December 10th. The catalogues have just arrived, and they’re beautiful.

RB: Did you ever imagine in 1975 that there would be a future in all of this? By 1977, the Sex Pistols were famously singing “No Future,” and for them, the refrain was accurate. Despite CBGB and even the Max’s scene being a bit less of a pose than Pistol Mania, New York still trafficked in a fair amount of excess, including a dash—or a dose, if you will—of self-destruction. How and why do you think the magazine survived, not only in spirit but as a creative and tangible milestone of the mid- to late-1970s Punk scene?

JH: I’ve made several attempts to relaunch the magazine, and a lot of people told me I was out of my mind. They thought I was trying to recapture my youth, but really I was just protecting my intellectual property. I always saw a future, and I thought PUNK Magazine would become the next big thing. I thought the Ramones would be the new Beatles. I thought Punk Rock would become a big thing too, and I was shocked when it wasn’t selling a lot of records and really surprised by the backlash. Even (then-President) Jimmy Carter went on a campaign against Punk—radio stations also. And the Sex Pistols, they never really accepted the term, and I think the Dead Boys (at CBGB) were first to jump on the (Punk) bandwagon. Besides all that, PUNK Magazine Issue #1 with Lou Reed on the cover came out months before the first Ramones record. Lou had just released Metal Machine Music—an album of noise and feedback that was like a nuclear bomb in the music industry—and you know, it paved the way for Punk. I could not have thought or dreamed of a better cover or interview for Issue #1 than Lou Reed.

RB: Well, at some point, despite the backlash—possibly after the fact or even right after Issue #1 came out—you must’ve known that Punk and PUNK Magazine were happening. What was it like finding yourself in the thick of it and having a fly-on-the-wall perspective? Did you ever experience moments of disbelief?

JH: Oh yeah! Like when I got the interview with Lou Reed, I jumped up in the air, and I was screaming, “I got it!” Then I saw the magazine on a newsstand, and that was a miracle to me. Lou (who claimed he’d forgotten about the interview) saw it too, picked it up, and he loved it. All these people saw it and were like, “It’s so great, WOW.” I was like, “Yep!”

RB: Given how strange and fleeting the passage of time can be, did you ever think about a PUNK Magazine legacy—or, for that matter, your own legacy as an artist and illustrator? When you started out, was everything simply of and for the moment? Who encouraged you to keep everything safe and organized and to handle with care, all of your writing, drawings, and everything connected to PUNK Magazine? Yale’s Rare Book & Manuscript Library was certainly impressed when it acquired your papers and the PUNK Archives in 2012.

JH: Well, I kept it all—or tried. I kept a lot of the art, storyboards, manuscripts, all that. I (eventually) lost the office, and I lived in a small apartment, so it was tough to hang on to everything, but you know, it’s my baby. Then I got to know Johan Kugelberg of Boo-Hooray Gallery, who’d been buying one or two things from me, and he brought up the idea of selling my archive to an institution. I had done the book, Best Of Punk, so he put together a wonderful exhibit at Boo-Hooray. I probably could have made more money over the years selling it piece by piece, but I wanted it to be a collection somewhere. I knew at Yale it would be taken care of.

RB: OK, John, so based on the magazine covers and much of its content, it’s easy to see your talent as a draftsman and social commentator, but I have to ask—were you the first to refer to the scene and the music as “Punk”?

JH: Oh no. The word was all over the place in late 1975. I remember Patti Smith and even Bruce Springsteen being called punks. I even knew (the term) Punk Rock from Cream Magazine, and, you know, I was a huge Alice Cooper fan—that’s what got me into this stuff.

RB: Thanks for a great interview, John, and bless Alice Cooper!

View this post on Instagram

***

50 Years of PUNK

At Ki Smith Gallery, 170 Forsyth St, NYC 10002

On show through mid-January, 2026

INTERVIEW Richard Boch

FEATURED IMAGERY ©️John Holmstrom 2025; Sex Pistols Puppets by Rose Lasagne

Richard Boch writes for Roxy Hotel’s Made In New York stories column and is the author of The Mudd Club, a memoir recounting his time as doorman at the legendary New York nightspot, that doubled as a clubhouse for the likes of Jean-Michel Basquiat, Keith Haring, Debbie Harry, Talking Heads, and many others. To hear about Richard’s favorite New York spots for art, books, drinks, and more, read his Locals interview—here.