The Beat Goes On: Remembering Drummer Clem Burke

To mark the opening of Clem Burke Photographed by Chris Stein at the Roxy Hotel, Richard Boch speaks with Debbie Harry, Chris Stein, Marky Ramone, Chris Frantz, and Jay Dee Daugherty about the legendary drummer and their memories of him.

Memories are a funny thing. They come and go; sometimes they fade, while others remain crystal clear. Occasionally, we remember things differently from what someone else might recall, or we may have a moment when something or someone stirs a memory that had left us long ago. Like I said—memories are a funny thing.

Clem Burke was an incredible musician, and he leaves behind a vast musical legacy that provides far more than just the memory of a remarkable era of music. Together with Debbie Harry and Chris Stein, he was a founding member of Blondie, recording eleven albums with the band between 1975 and 2017. He was on the road with Blondie in mid-2024 when his health got the better of him, forcing an end to that year’s tour.

Arguably one of the all-time great drummers of Rock ’n’ Roll, Clem’s firepower and finesse were more than just the beat. When his rhythm and timing locked in with Debbie’s vocals and Chris’s lead guitar, it was the engine that propelled the band to the top of the charts. Beyond memorable in every way—just listen to the opening twenty-plus seconds of Blondie’s hit “Dreaming,” and you’ll get it.

During Burke’s more than five decades as a recording and touring musician, he played with everyone from Ringo Starr, Bob Dylan, and Iggy Pop to the Eurythmics, the Go-Go’s, and Nancy Sinatra—yes, Nancy Sinatra! Drummer Jay Dee Daugherty of Patti Smith was moved by the way Go-Go bassist Kathy Valentine’s memoir, All I Ever Wanted, paints a tender portrait of Clem Burke as a former lover, and then a forever friend.

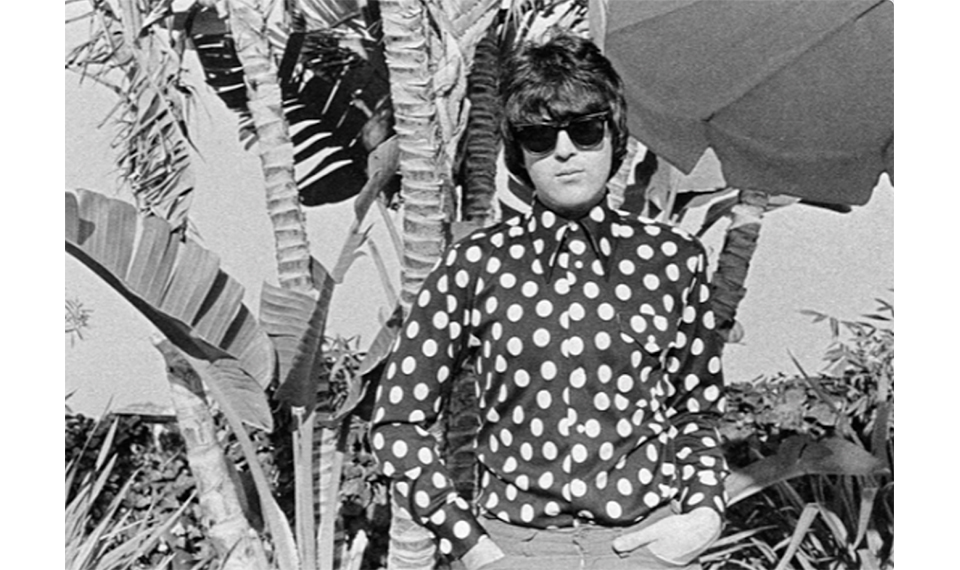

His range and influence are undeniable—into the realm of what can easily be referred to as legendary. Burke’s sense of style—from his haircut to a suit and tie and polka-dot shirt—along with his ability to engage, whether backstage, on the street, or hanging at the bar—were known to be quite memorable too. Seen through the lens of bandmate and photographer Chris Stein’s camera, the memory, the vision, and in a strange way even the sound of Clem Burke’s essential contribution to Punk, New Wave, and the entire canon of Rock ’n’ Roll comes into focus.

I recently took the opportunity to ask Debbie Harry, as well as several of Clem’s peers and contemporaries—all of whom were key players in the music scene once centered around CBGB—to share a memory of Clem Burke. I quickly found there was no shortage of love, respect, and admiration. The Ramones’ longtime drummer, Marky Ramone, shared those feelings in the clearest way when he told me, “Clem was a drummer’s drummer who truly loved playing. He had an infectious lust for life, a big heart, and was a real gentleman. He brought a lot of joy into the world, and his sound lives on.”

And that’s just the beginning.

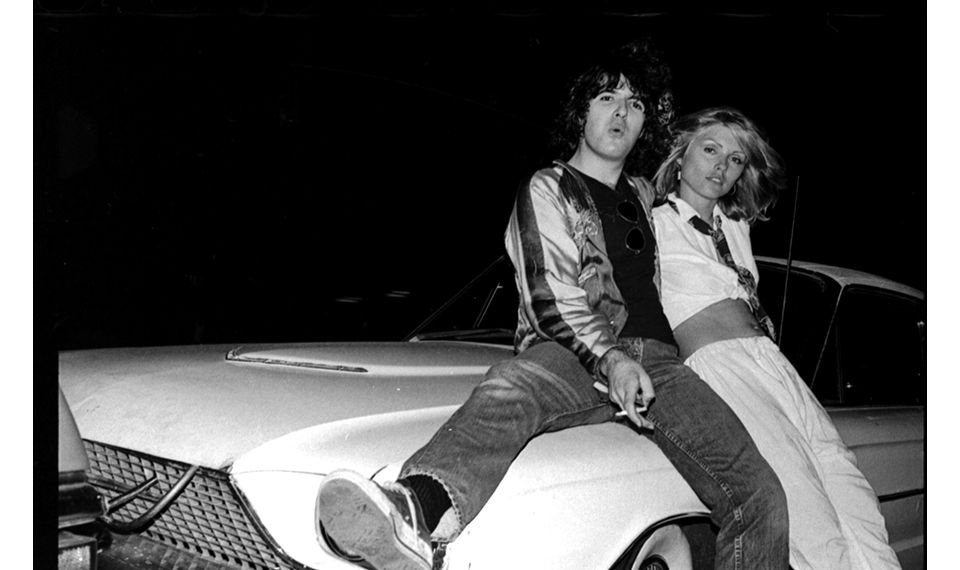

Clem and Debbie in front of CBGBs, c. 1974-75. Photographed By Chris Stein.

Richard Boch: Hi Debbie. It’s difficult to think of Clem in the past tense, given all the music he’s made with Blondie as well as with a number of other great bands and musicians. Your relationship, however, tracks next level with Clem—not only was he an original and lifelong member of Blondie, but he was an essential part of what you surely consider family. What do you feel when you think of Clem, and is there a moment or memory that best describes that feeling?

Debbie Harry: After working with Clem since 1975, I’m proud to say we were still speaking, still playing live, still touring—and most importantly—still recording music together. That’s something not every band can claim. It’s a testament to just how difficult it is to keep a group of freewheeling musicians literally on the same page. Through it all, Clem remained dedicated to Blondie. He was our standout stylist, musician, and showman—a loyal, integral part of the band for the entire 50 years we were together.

Gary, Debbie and Clem, Lime Street Station, Liverpool, c. 1977. Photographed By Chris Stein.

RB: Hello Chris. Thinking about the early and somewhat incestuous days of Punk, there were several bands that certainly would be considered the headliners. Your band, Talking Heads, together with Blondie, Patti Smith, Ramones, and Television were the biggest of the big names at CBGB, Max’s, and to some extent, though less of a music venue, the Mudd Club. You were the Talking Heads drummer, and your band occasionally shared the bill with Blondie. When you think of Clem, and even yourself, for that matter, did you have any idea that history would not only remember but cherish those legacies?

Chris Frantz: When I first met Clem, it was the spring of 1975 at CBGB. He had only just become the drummer for Blondie. He was a friendly guy, very enthusiastic about Rock ’n’ Roll music, who had grown up across the river in Bayonne, New Jersey. He had shoulder-length curly black hair, a fresh face, and what I had come to recognize as a “bridge and tunnel” look.

We had different backgrounds and personal styles, but that didn’t matter, because we had mutual respect for each other—even though our drumming styles were completely different. All the drummers playing at CBGB had their own thing, their own unique style.

One night, Clem sidled up to the bar and asked me if he reminded me of anyone. He was sporting a whole new look with a slim-fitting black suit, white shirt, Beatle boots, and a new wave haircut. Then Clem said, “Some people say I resemble Paul McCartney.” I smiled and told him that I saw more of a resemblance to Dino Danelli, drummer of The Rascals. In fact, to me, Clem’s drumming style reminded me more of Dino than it did Keith Moon or anyone else.

Clem and I never had any doubt that our bands were going places. We both loved being in bands, and we had a strong work ethic. We had determination. Nothing was going to stop us.

In more recent times, we lived in different parts of the country, but occasionally we would bump into one another and greet each other warmly. We liked to reminisce about that time in Glasgow, Scotland, when Talking Heads was on tour supporting the Ramones, and Blondie was on tour supporting Television. It was incredible to us that all four of these CBGB bands were playing in the same town in Scotland at the same time. Clem came to our show that night to show his love and support.

What a wonderful thing that Blondie and Talking Heads and so many of our CBGB friends have arrived at a point where we can see that our legacy is loved by so many. This feels fantastic to me, and I know it was especially rewarding to Clem. I’m sorry he’s gone, but I’m happy he lived to witness his own enormous impact on Rock ’n’ Roll.

Camouflage. Clem in LA, 1977. Photographed By Chris Stein.

RB: Hello Jay, I realize that you’re ready to head off on the Patti Smith Horses 50th Anniversary Tour—a reality both well-deserved and unbelievable at the same time. Remembering, if possible, standing around the bar at CBGB or on the sidewalk outside, was there a connection or a sense of camaraderie between bands, whether you were sharing a bill or not? Did it seem even remotely possible that you and fellow drummers like Clem Burke or Chris Frantz, or Marky Ramone would share not only a legacy born of the mid-Seventies New York Punk scene, but would influence and inspire several waves of next-generation musicians?

Jay Dee Daugherty: My first memory of Clem was watching him play at one of Blondie’s first shows at CBGB—which, in those days, was unfathomably the only place in New York City where an unsigned band could even get an audition, let alone land a gig. Word spread quickly amongst the most ambitious of the latest wave of art immigrants who had decided to incubate in the city’s edgy, repugnant beauty. Being the only game in town, the hotbed of CBGB became the focal point that ignited the fire of that era’s disparate creativity, resulting in the emergence of the five artists that defined that scene: Television, Patti Smith, The Ramones, Talking Heads, and of course, Blondie.

It was an incredibly small scene. You would always see the same fifty people at every gig or art opening. It was congenially competitive on the surface, but like being on any team, you know your team is the best. So best. No question. And having been a huge fan, miraculously finding myself on Team Patti, I had decidedly intense druthers and prejudices. In my book, there was nothing or no one, before or since, who could match her intensity, originality, sensuality, style, and shocking song-within-a-song improvisations.

But Blondie? They seemed like a throwback—on-the-nose future-retro nostalgia—that felt against the grain of the current trajectory and too referential to the eras we were trying to get ahead of, or so we thought. But then again, when I heard the first Led Zeppelin record, I thought they were a performative, shouty mound of macho blues pilferers going nowhere. So, what do I know? Live and learn, indeed. Snobbyness is a tonic unto itself. Apologies to all Blondies, past and present.

But Clem? Oh, yes—wasn’t this about him?

When I saw him playing so intensely with Blondie, I felt a combination of surprise, joy, admiration, and envy that he was in a band where his wildness ran free but was vital in defining the band’s sound. It was obvious that he, like me, adored Keith Moon, who no one has been able to imitate (although Zak Starkey made it to the closest Zip Code). With Blondie, Clem was able to integrate just enough Moon-ness to propel things without it going off the rails—a successful and delicate dance between order and a flirtation with chaos. There was a drummer, oh-yeah, heart/recognition.

And the dude was undisputedly on style-wise, the heat of the stage be damned—never not looking fully dressed, top button buttoned and ready for his deserved close-up. And that hair! I wish I had made more of an effort to know him better than our occasional at-the-bar small talks over the years; I’m quite shy. But everyone I know who did know Clem makes the same report—totally sincere and enthusiastic to a fault, ready to play at the drop of a hat (a Trilby, it would have to be). And he did play with everybody, those who asked and apparently some who didn’t. He’d just show up on the drum throne.

And do rock on, dear Clem. Well done.

***

Chris Stein’s photographs of his bandmate Clem Burke certainly speak to Clem’s memory and legacy—and along with Chris’s closing words, offer a loving coda to a life well lived.

“Clem was the heartbeat of Blondie—essential to our sound, our success, and our spirit. He’s always been a student of popular music and culture, constantly inspiring us with his energy and drive, always saying, ‘Let’s get it going—we can do this!’ Over the years, Clem has delivered countless iconic punk moments, and these photographs capture some of his finest.”

— Chris Stein

***

Clem Burke Photographed by Chris Stein is on view at The Roxy Hotel through January 6, 2026.

INTERVIEW Richard Boch

FEATURED IMAGE Clem on Kings Road in London Next to a Television/Blondie Poster, 1977. Photographed By Chris Stein.

Richard Boch writes GrandLife’s New York Stories column and is the author of The Mudd Club, a memoir recounting his time as doorman at the legendary New York nightspot, which doubled as a clubhouse for the likes of Jean-Michel Basquiat, Keith Haring, Debbie Harry and Talking Heads, among others. To hear about Richard’s favorite New York spots for art, books, drinks, and more, read his Locals interview—here.